Dying Crafts in Ipoh

Cover Story

By Khaleeja Suhaimi

The late Yasmin Ahmad once remarked that Ipoh is one of the maddest places she has ever stepped foot in. Strolling through the streets and stumbling upon the locals, I’m sure most will agree with this. Back in the days when Ipoh was known for its tin-mining, it was also known for its authenticity in crafts. However, as time passed and technology became the norm, these crafts dwindled along with most of our appreciation towards them. Today, the only people who truly find value in these crafts are the craftsmen themselves. In fact, as hopeful as they can be, even they don’t see the light of day anymore. Where did the appreciation and gratitude we once carried in us go?

Artisans Who Wouldn’t Give Anything Up For Their Crafts

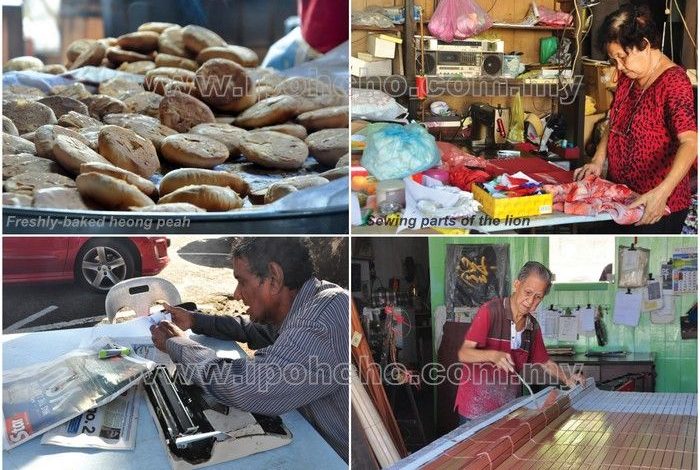

Traditional Heong Peah Making

Lew Yung Boon, who began working in 1988, has never left the traditional heong peah (fragrant biscuit) making since his first day of work.

“This business belongs to my close friend but he’s over 70 years old now and can’t work much. That’s why I’m here to help him out,” he said.

Going back to 1981, Gunung Rapat has been famous for its heong peah making. Until today, one of the most well-known brands is Yee Hup and people from all walks of life still get it as souvenirs.

Heong peah is a crispy, flaky biscuit with sweet fillings. It is mainly made up of oil, flour, sesame seeds, maltose, sugar and shallots. The sesame seeds play a role in creating the signature fragrance.

The traditional way is done by sticking the pastry dough to the inner walls of the traditional barrel ovens. The reason why the biscuits are done in an oblong shape is to counteract gravity’s force in the oven so the biscuits wouldn’t fall into the fire below.

The fire is kindled with coconut husk, kept alive and timed by workers to control the temperature. This is a task requiring skill and not many are able to handle this task as the risk of getting biscuits burnt or undercooked is high.

Usually, the coconut husks are kept alight for around one hour before sticking the pastry dough. Once the dough is pasted to the sides of the oven, it only takes about 15 minutes for it to turn brown and flaky. If the bottoms get too charred, it will be scraped off.

“This process gives the biscuit a more authentic essence, character and aroma altogether. You can tell the difference between an electrical oven heong peah and a traditional-made one just by the fragrance itself,” Lew told Ipoh Echo.

However, most shops use electrical ovens these days for a quicker process. Besides, the traditional barrel ovens can only broil up to 200 biscuits. Priced at RM9 per pack, its freshness is guaranteed.

No. 362 is among one of the remaining houses which still practises this process in Gunung Rapat. Some of the other houses include Seng Kee Food Trading and 189 Heong Peng Ipoh, which are located along the same street.

Address: 362, Jalan Gunung Rapat, Gunung Rapat, 31350 Ipoh. Opening hours: Every day except Sundays, 6.30am till 6pm Contact: +605 311 3529 or +6016 560 9094

Wooden Clogs

Located in the midst of the busy streets and food havens, 68-year-old Yao Cai Yu is still very keen on making wooden clogs. It has been her forte for over 30 years and she hasn’t planned to stop.

“I learned the skill from my mother-in-law. In the olden days, it was almost a must for every Chinese to have a pair at home,” said Yau.

She travels from Taman Cempaka daily, taking the bus. She has four children, who aren’t interested in taking over her business. Her husband used to come by to help out but he’s aging now and it’s getting tough for him.

“I don’t blame them. I understand that the younger generation are different compared to our time,” she said.

The business began operating when her parents-in-law arrived from China. At that time, clog soles were still handmade. The shapes were cut out using an axe before they were planed smoothly.

When she took over, they had already begun using machines. Thus, her job was only to get the plastic skin, consisting of various colours, nailed on the clogs. As simple as it may seem, Yau’s work actually requires patience and hard work.

“Of course there aren’t as many customers as I had before. The market is slowly fading away and wearing clogs is no longer a tradition,” she expressed.

It would be a rare sight to witness a passer-by in clogs today. Most of them only have these clogs at home especially to go to the bathroom. One pair costs RM7.50, depending on size and design.

Address: Central Market, Jalan Dato’ Onn Jaafar, 30000 Ipoh. Opening hours: Mondays till Saturdays (8.30am to 3.30pm), Sundays (8.30am to 2pm)

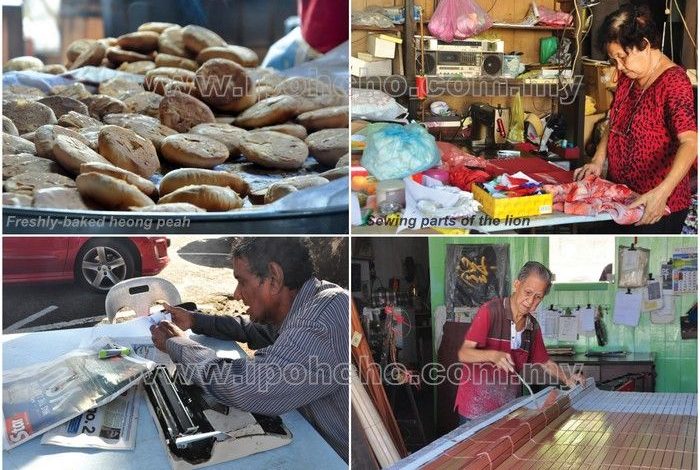

Petition Writing

“When I was 19, I came across so many petition writers around town and I said to myself I wanted to be like them. I wanted to type,” said Ezekiel Velu, one of the few remaining petition writers around.

Sitting under the tree in front of the State Mosque along Jalan Dato’ Sagor, Ezekiel has been working as a petition writer for over 50 years now. The father of four boys and one girl says that although his children are well-off, he never wants to quit. At least not yet.

“I don’t receive as many customers as I used to in the past. Now, only my regular customers and those who’ve known my work still come,” he said.

Ezekiel was a former office worker and is still using his skills to type out legal documents such as applications, wills, tender papers and anything related to it. Besides his passion towards his job, he also participates a lot in church work.

“It’s like having a dictionary in the back of your mind. Hence, I never draft anything beforehand. Once I insert the paper in the typewriter, everything flows out,” continued Ezekiel.

While there used to be around 40 of them, now the only ones left are Ezekiel and another dedicated Chinese petition writer who works nearby. Since computers are so widely used, Ezekiel doesn’t see the point of petition writers anymore because he believes that the generation today are not interested in a job like this.

“I can complete typing out one full page in around five minutes. The only details I need are their name, address and essential information, depending on the document,” he exclaimed.

With much precision in his work, Ezekiel charges each document reasonably. He mentions that the job keeps his mind active as he comes across different people every day.

Working hours: Weekdays, 8.30am to 2pm Location: State Mosque along Jalan Dato’ Sagor Contact: +6016 559 1202

Lion Head Maker, Kin Teck

Lion dance is often seen during Chinese New Year. It is said to bring good fortune and the symbolic meanings may vary according to different types of food, fruits or vegetables used in the ritual.

Here in Ipoh, 74-year-old Tan Khar Mee is probably among the only few lion-head makers left in Malaysia. Kin Teck used to be a sundry shop.

Tan learned this craft at the age of 11 from his uncle who hailed from China. He has been doing so for more than 40 years. He now works with his wife, Soi Lai Fong who usually works on the body parts.

“Most of the people who came to learn eventually never came back. In fact, there were two who took it seriously. One was from London who came by for three months to learn. The other one from Kuala Kangsar didn’t continue and opened a mini market,” said Tan.

There are two types of lions: Southern and Northern. The Southern one is related to the legend of Nian, a monster which resides in the mountains or under the sea. Many people mistakenly refer to the lion as a dragon too, which are both different.

“Lion heads can be completed within 10 days while the dragon one takes one whole month. It’s harder to make and isn’t really popular in business due to the price which ranges from RM5000 to RM25,000,” he continued.

Unlike the dragon head, a lion head costs up to RM2000. As the years passed, he began designing his own dragons, having the statues he sees on the roofs of temples as inspiration.

The process involves binding the thin bamboo pieces to form the head shape, using pieces of paper. Other materials include aluminium, paper and cloth before painting. Tan gets the bamboo from the outskirts like Parit and Papan.

“I can do different shapes too, like mosquito, fish and hornbill of various colours. My children don’t want to take over the business but I’m happy to welcome anyone who’s interested to learn,” said the sifu himself.

Address: 4, Market Terrace 30300 Ipoh. Contact: +605 255 8511 or +6012 455 3242

Lau Hooi Kee Chick Blind Maker

What started off a century ago by Lau Cheong from China is now in the hands of the family’s third generation, Lau Chee Wah. He has been operating this business since the early 60s.

Lau and his 10 other siblings have been exposed to the industry ever since they were little. Despite the generational longevity, they have never once hired a single staff. Lau expresses that a single worker costs so much these days, how could he afford to hire?

During the 50s, bamboo blinds were said to last longer than wooden ones, which was why they were rather popular. At that time, bamboos were cut by the Orang Asli who lived all over Perak. Unlike today, raw materials used to be cheap. Now, Lau cuts the bamboo and wood by himself.

Price range varies according to measurement. It would cost RM7.50 per square foot for bamboo ones and RM8.50 per square foot for wooden ones. The time slated to complete a small blind is only around four to five days while bigger ones would take a little longer.

“The industry is indeed passive these days and doesn’t receive as many orders as it did. Even if it were to be popular again, I wouldn’t know how to help,” he said.

Conclusion

The most astounding thing about these artisans is the dedication and commitment they put into their trades. Never giving up in whatever they do, it is definitely a reminder for us all to begin instilling the value we have forgotten through the years; appreciation. Hopefully once we truly appreciate, perhaps these crafts won’t be labelled as dying anymore.

Bamboo blinds are still seen today in older parts of the town. Most of the shops use it as an advertising entity and to keep away from the heat of the sun.

There used to be a machine, specialised for bamboo blinds but not much profits were made due to the permits needed.

“I only make money when there are orders. I’m not married so I don’t have anyone to pass this on to but as long as I’m still alive, I’ll make use of every second I have with this business,” Lau added.

Address: 15, Lorong Bijeh Timah, 30000 Ipoh. Contact: +605 254 2972