By Ian Anderson

The problem of unwanted babies has been with us for thousands of years. It seems that all too often, we can enjoy the fun without caring about the consequences. Often the problem was simply solved by infanticide. Others were, and still are, sold into a life of slavery. Child sacrifice to ancient deities and spirits also took its toll. These practices took place across the world and were very common during the Greek and Roman empires, where live babies were simply thrown on the local rubbish dumps and left to die; the lucky ones being rescued by good Samaritans and adopted as their own. China also has a long history of the disposal of unwanted babies.

For China, some people lay the blame at the door of the Chinese Government and its “One child a family” policy”. During that period some 40 million young girls went ‘missing’. A certain stretch of the Yangtze River was known to be a common site of infanticide by drowning until government projects made access to it more difficult. But this is modern history and does not consider those hundreds or thousands of years, that stretch back far beyond modern China. Infanticide has been commonly practised in China since ancient times and recorded in history since the 3rd century BC; by the time of the Song dynasty (960–1279 AD), it was said to be widespread in some provinces. At that time there was a belief held by some Chinese that newborn children were not properly “human”, and were not to be considered as such until after the sixth month after birth. Thus, in those early days, killing an unwanted child, mostly restricted to little girls, was an acceptable practice. But why choose to murder your female child?

Traditionally, in a Chinese family, there can be nothing more important than the male bloodline. Not too many years ago, even in Ipoh, male children “rule the roost”, while the females were virtually ignored. Fathers looked upon their daughters as an unnecessary expense. Anything spent on education was a waste of hard-earned money, as was the entire cost of bringing up a daughter. As soon as they were of marriageable age, daughters would ‘marry out’ and serve their new husband’s family. Until that day they could cook and clean and serve the males in their family.

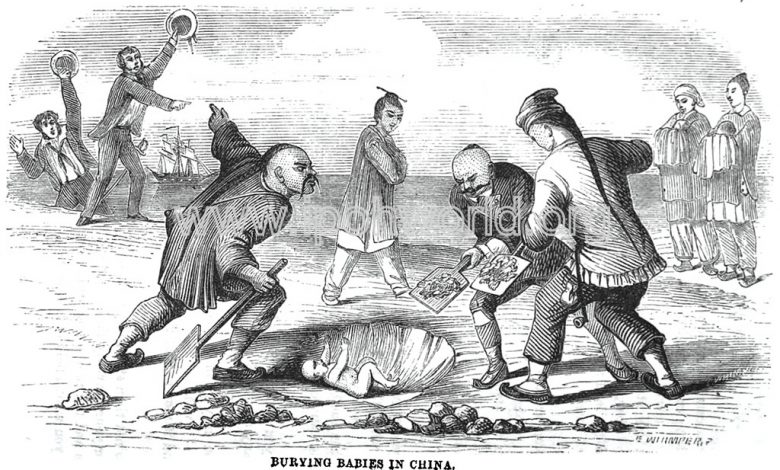

Much of the history of Chinese infanticide came to be known in the western world from the many Christian missionaries that travelled in China in the early days. To some extent, they were successful in their mission. Christianity in China appeared in the 7th century, during the Tang dynasty, but did not take root until it was reintroduced in the 16th century by Catholic Jesuit missionaries. The Methodists soon followed and as you can imagine were shocked and horrified when they first came across infanticide in China. They found live babies being buried alive on the beaches and later, in the 19th century, deliberate drowning of infants in water-filled pots as live burial was no longer generally acceptable. Like all missionaries, the Methodists sent back regular reports and many of these were published in The Methodist Magazine and Quarterly Review. An issue of the magazine in 1839 records: “Infanticide in Chine is wholly confined to the female sex” and “A boy is valued and cherished, while a daughter is despised”. In 1865, they then produced an etching entitled “Burying Babies in China”.

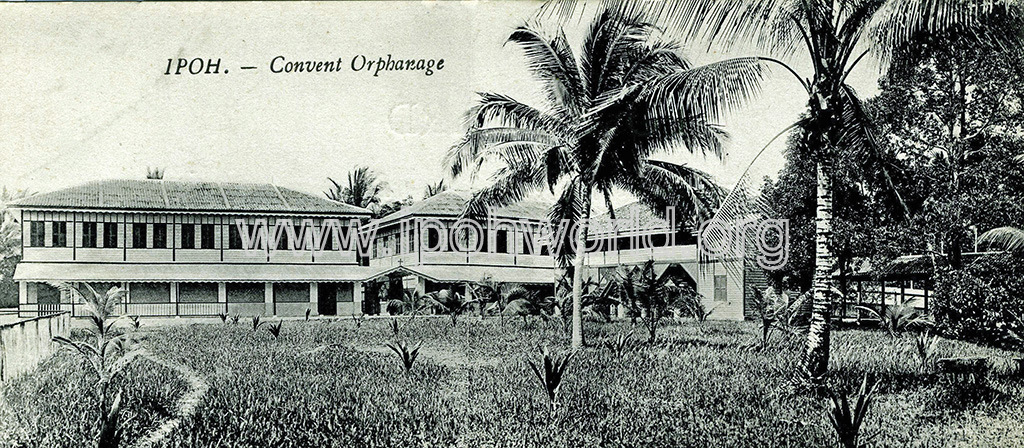

Ipoh had thousands of immigrant Chinese around the same time as that etching was produced, but thankfully, as they were almost all unaccompanied men, infanticide did not come with them. But as the years went by, Ipoh had many Chinese families and the problem of unwanted babies, again mostly female, reared its ugly head. Local orphanages were needed for the care for these poor waifs and two Christian organisations, the Sisters of the Holy Infant Jesus and the Elim Gospel Hall stepped into the breach. The latter’s first intake being six little girls from China in 1915.

Strangely enough, although infanticide was levelled at all Chinese, the Hakka dialect group had a better solution. Directly translated from the Chinese it is known as “Little daughters-in-law”. The basic premise was that if you had an unwanted daughter then you gave the girl to a Hakka family who had or was expecting a son. The two children would grow up together and when they reached the right age they would marry.

This was a very common system for the Hakka in Ipoh before the Japanese Invasion.

The Phoong family of Ipoh had six sons and one daughter. The only daughter, Ah Thye’s fate was sealed. As a youngster, she was given to a Chinese family who were returning to China. They had a son a little older than her. Her role was to be a “Little Daughter-in-law” to the family while waiting to marry their son. Unfortunately, he was a little “slow” as modern parlance has it and before long passed away from a high fever, never reaching marriageable age. In her later years, she often recalled that the one thing she was sorry about was that because of his difficulties she had teased him to the point approaching unkindness. No longer needed by her adopted parents, as soon as she was old enough she went to medical college and studied Bacteriology. While working as a hospital nurse, she met a Kuomintang General and subsequently joined the Kuomintang army as a nurse.

With six sons, the family gladly took in four Little Daughters-in-Law. Sadly, two of the little girls died from eating poisoned berries growing close to their wooden house. No more little girls joined the family.

Descendants of the family and the Little Daughters-in-Law still live in Ipoh.