Four years ago Setiawan-born teenager Nathaniel Diong developed an entrepreneurship education programme to equip youths with the necessary interpersonal, communication, and practical skills demanded by employers. The programme is run in secondary schools and universities across Australia, Britain, USA, and Finland. Now an Australian, he was only 16 when he read an academic paper that pointed the way to a bright future.

Another ex-Perakian, Ipoh-born Rupa Shanmugam, studied electrical engineering and later established herself in New York where she joined a leading technology firm and rose to become its president and CEO.

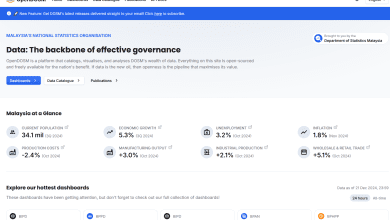

Emir Research has put the figure of Malaysians leaving the country at two million since the 1970s, with some 500,000 falling into the highly skilled category. A survey conducted by Randstad Workmonitor three years ago showed that 90% of the respondents were prepared to move to another country.

Are there severe implications that could negatively impact everyone in Malaysia? Yes. For one, a brain drain of this size means there is major dissatisfaction with the direction of the country. A big source of discomfort is the repeated attacks on the use of English. The latest salvo came early this month from the president of a political party in government who slammed English language users as having a colonial mindset.

The colonial trap of language would have been true before Merdeka, as the intention then was to ensure the colonised people understood the colonialists and carried out their orders. But the English language has not been used for any colonial purpose over the past several decades.

In fact, many leading politicians in Malaysia seem unaware that English has developed a global character, shooting out a trunk that will in decades to come likely be known as International Standard English. While British English is the root, International Standard English will reflect diverse inputs from many regions, particularly India and China.

The push for International Standard English will come from global influencers who have long seen the need for one international language to facilitate real-time information sharing. There is only one language out of thousands that meet all the criteria — English. Other languages will continue to play strong regional, national, local, academic, or cultural roles. However, nothing can beat English as a worldwide bridge-builder.

What makes English the only suitable language for this global role is its widespread use across the entire globe, both in terms of the ethnic diversity of users and also in terms of its important function across all fields of endeavour such as diplomacy, religion, business, and science. Mandarin is spoken by more people than English, but China has no intention of pushing Mandarin to replace English or compete with English.

What if every nation does push its own national language into competition with English? International diplomacy may collapse. While it is salutary to deliver your speech in the national language, it is disastrous if you avoid speaking English altogether. Imagine crossing the lawn with a foreign diplomat on your way to a conference venue. You talk your lingo and he talks his lingo. Each of you needs to bring along a translator.

That is an added cost. What if the translator mishandles a few terms, misses some nuances, or literally translates an idiomatic expression? Furthermore, direct brain connectivity between the two diplomats will be harder to establish. Eventually, after one round of miscommunication, the two diplomats will avoid talking to each other. Do you prefer to be effective and fruitful in diplomacy, or do you prefer to display your culture?

To establish rapport with other nations, there must first exist a common base for all to stand on. One reason that Asean has done well is simply that English is its working language. With this as their common base, the diplomats of all 10 member nations have no fear of miscommunication through poor translation. Abandon English, and Asean will turn into a hot pot of insular nationalistic displays with no common direction.

Why is the United States winning the public relations war against China? It’s largely because China’s President Xi Jin Peng rarely speaks English. When American President Joe Biden speaks, more than half the world listens and understand his words. When President Xi speaks, only a corner of the world listens. It is ironical that Biden is winning the PR war, because Xi has more substance and more creative ideas for humanity.

Religion will be another big casualty in any move to abandon English. The availability of English translations of all scriptural texts of every religion in the world has helped foster interfaith dialogue and understanding. Without English, all the religions will treat each other with deep suspicion and fear as the non-adherents don’t know what’s in your scripture and will fall victim to scam commentaries.

Drop English, and the economy may shatter to pieces. English is the language that all industry people of standing use. If you’re a foreign buyer, you obviously prefer dealing with a Malaysian producer who can speak English. You get your point across directly each time you have a problem. If buyer and seller do not use a common language, it’s a duck talking to a goose.

Finally, the principal language of science is English. It is clearly impossible to translate all scientific works into Malay or Tamil or Mandarin, nor will there be any keenness to do so because it will cost millions of ringgit every year in translation fees. And how many qualified translators do we have who can handle scientific works?

Scientific research and linguistic nationalism stand in opposition to each other. Several thousand research papers are written every year, mostly in English because that is the main language for peer review. To gain acceptance, your research paper has to pass review by a panel of experts. If you write your research paper in non-English, who is going to review it? Your neighbour, who has no credibility?

Significant discoveries leading to the spread of new knowledge are published in English-language journals, magazines, and books. If you can’t read English, you miss out. Malaysia’s global ranking for English proficiency has dropped from 12th position in a field of 77 nations to 28th position in a field of 112 nations over a six-year period. The English Proficiency Index can be used as an indicator of a nation’s share of global voice.

Singapore occupies 4th spot — a clear sign of its growing prominence. One nation to watch is China which has climbed from a low score to moderate score just behind India over these six years. What is the worst implication of Malaysia’s shift away from English? We are throwing away the key to new knowledge that is every day being discovered. Without this key, our people will live in a mentally confined space, a prison of the mind.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Ipoh Echo